The Fed is Playing a Dangerous Game Holding Off On Rate Cuts

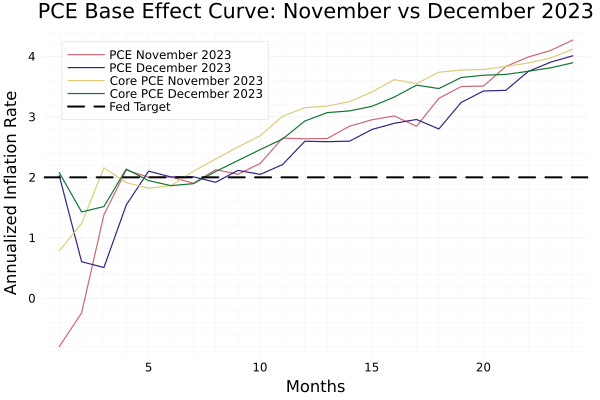

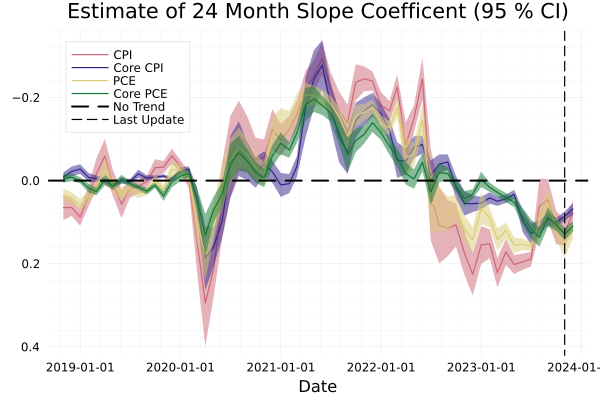

In my first post I visualized how the timeline over which inflation is measured effects what it is measured as, creating something I called the Base Effects Curve. using this curve, i estimated a slope coefficient, and showed that when this coefficient shows a statistically significant deviation from zero with more than 95 percent confidence, it is inversely correlated with annual inflation rates six months into the future.

Since I finished writing that post, only a few data points have come in, but they do--at least so far--align with my prediction that inflation would continue to decline this year. Especially when examining the Federal Reserve's favored gauge of inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE), both curves have shifted downward across most durations. Furthermore, in the latest data release, a greater portion of each curve is either below or in close proximity to the Fed's 2 percent target compared to the data presented in the previous post.

Moreover, all four measures of inflation, whose curves I monitored, retained slopes that I could confidently assert were positive with a 95 percent confidence level1. If the correlation I showed in the first post holds, in six months, annual measures of inflation will be lower. Right now, inflation cannot come down too much before reaching the Federal Reserve's target.

These data points preceded the FOMC's most recent meeting, and yet in its most recent announcement and Chairman Powell's subsequent press conference, the message has been one of extreme caution, with the Fed doing little more than removing its bias towards hiking interest rates in the immediate future. Intuitively that should not be a problem. After all, the Fed is the most important financial institution in the world, it should need more than a simple correlation posted on the blog of a grad student. Especially if that poster has a vested interest in easing financial conditions going into an election year. After all, how much damage can the Fed do by keeping things the same?

A lot of damage, as it turns out. For two reasons: interest rate hikes act with "long and variable lags," and the structural dynamics of real interest rates.

The idea of "long and variable lags" refers to an observation first written down by the Milton Friedman that the macroeconomic effects of monetary policy are not immediate. There are many different mechanisms by which monetary policy effects the economy, and it depends on the structure of the economy how influential each of these mechanisms will be. What that means right now, seven months after the Fed last hiked rates, is that the full economic effects have probably not been felt yet. A lot has been written about the concept, and I do not have a lot to add, so I will move on to the structural dynamics of real interest rates. If you want to know more about the concept, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published an explainer last year.

As to the structural dynamics of real interest rates, I am slightly alarmed that they are not more prominent in discussions of the Fed's current policy. Therefore, I will spend the rest of this post explaining why they are important, and why the Fed should be more concerned with them than with their perceived credibility.

What The Fed's Interest Rate Decisions Actually Do

Whenever the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) convenes, they establish an upper and lower range for the Federal Funds rate. This range dictates the rates at which banks will either pay or receive funds in the overnight borrowing market. Due to the perceived security of this market for lenders, the rate set within it tends to serve as the baseline for all other borrowing rates. Consequently, by adjusting this rate, the Federal Reserve (Fed) can influence the rates that all other borrowers must pay, leading to significant macroeconomic consequences.

For businesses, higher interest rates represent an expense that diminishes their profit margin. Consequently, elevated interest rates often result in fewer investments. Similarly, consumers relying on borrowing for purchases will either reduce their spending or allocate less money to other consumption, as a greater portion of their income goes towards interest payments.

A crucial distinction exists between the interest rates mentioned in the first paragraph of this section and those in the second. For businesses and consumers, what holds significance are real interest rates – that is, interest rates minus inflation.

This distinction is crucial because borrowers make their interest payments in the future. If dollars are anticipated to be worth less in the future, obtaining them to fulfill interest payments becomes more manageable. Thus, when interest rates rise, the impact on borrowing costs depends on the simultaneous movement of inflation rates. In our current context, as inflation declines, borrowing becomes more challenging unless interest rates fall correspondingly. This relationship is explained in the Fisher equation: $$ r = i - \pi $$ where the real interest rate is $r$, nominal interest rate is $i$, and the inflation rate is $\pi$.

Measuring the Real Interest Rate

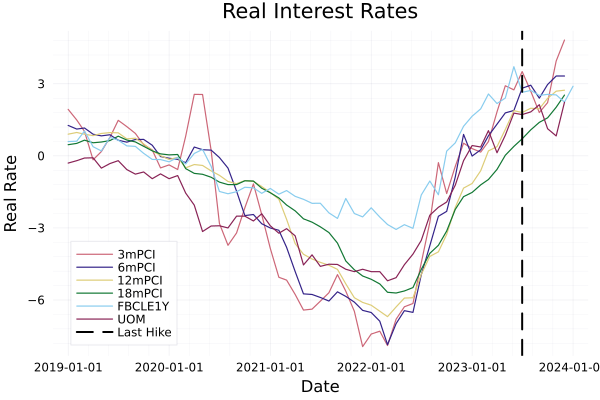

For the same reason that measuring current inflation is tricky, gauging the real interest rate is tricky. There are roughly three approaches, two of which are forward-looking, and one of which is backward-looking.

The backward-looking method is the simplest, involving subtracting a current measure of inflation from the existing federal funds rate to estimate the real interest rate. Despite its simplicity, this method has its flaws. Borrowers are more concerned about inflation over the course of their loan rather than in the preceding months and years.

That leaves the forward-looking approaches. One involves surveying businesses or consumers about their expectations for future inflation. While this approach has the advantage of surveying those who will actually be borrowing, historical data indicates that these estimates consistently overestimate future inflation.

The other commonly used forward-looking approach is to use financial market data. In addition to selling bonds with a fixed interest rate, the Treasury sells inflation-protected bonds that adjust the principal tied to them according to CPI inflation. As a result, the difference between the market yield of normal treasuries and TIPS of a given duration give insight into what investors think inflation will be over the future. Unfortunately, this measure is also flawed. The market for normal treasuries is much deeper, and as a result their prices (and yields) will be higher (lower) due to the fact that a deeper market means that more investors will be able to unload their positions without moving the market. The exact size of this "liquidity premium" can be hard to assess.

Therefore, it can be helpful to look at all three measures. The Cleveland Fed helpfully compiles all three of them into expected inflation measures.

Because of the debate over how to estimate the liquidity premium, I declined to plot it directly. Rather, I plotted the path of the real federal funds rate according to four vintages of PCE inflation, the Fed's preferred measure, the University of Michigan's survey of consumers expected inflation one year ahead, and the Cleveland Fed's compound inflation expectation for one year ahead.

No matter which measure I choose, the data shows that real rates have continued to increase followed the Fed's last hike. This trend shows no sign of stopping, which means that the longer the Fed holds rates constant, the longer real financial conditions will continue to tighten. If they do, they risk sending the economy from a soft landing to a hard one.

Credibility: Why The Fed's To Priority isn't a Good Economy

Legally, the Fed has a dual mandate2 for stable prices and full employment. However, there is ample evidence suggesting that the former takes precedence.

That prioritization is not without some merit. In a world where the reserve currency of the world is backed by nothing but the confidence of the people who use it the, the stability of its value is of paramount importance. Especially to the authority in charge of that currency.

One of the tools the Fed uses to make monetary policy is to provide what is called "forward guidance:" an expected path for future monetary policy decisions provided there are no data surprises. This policy tools is only effective if market participants believe the Fed is credible in the information it puts out.

That is why the pick up in inflation that started in the second half of 2021 was so damaging to it. Fed leadership had been reassuring markets that inflation would not pick up, and when it did it took what felt like a long time to actually start raising rates.

And while I think that there is a strong possibility future economists will look back at this inflationary episode as transitory, it certainly did not feel that way at the beginning of 2022, and many people lost some measure of trust in the Fed due to its adherence to the view that it was.

The Double Edged Sword that is Independence

The Fed has a great degree of statutory independence from elected officials. While the President appoints and the Senate confirms members of the board, short of enacting legislation, the executive and legislative branches have fairly limited power to control Fed policy.

This independence has two benefits to the practice of monetary policy: it can be unpopular, and it can be fast. Famously, the long-serving Fed Chair William McChesney Martin said the Fed was in the position to take the punch bowl away just as a party is heating up. Less famously, Paul Volker told Alan Blinder that his policies brought inflation down by "causing bankruptcies." 3 Because the public cannot easily change Fed policy, it can pursue unpopular, but necessary policies to stabilize or improve macroeconomic conditions.

Similarly, the Fed can act much faster than the elected arms of government. For example, even though the initial policy response to the pandemic in the form of the CARES Act passed about as quickly as any similar legislation ever has, it still took weeks longer than the Fed did to cut interest rates to zero and reinstitute quantitative easing.

This level of power in an essentially unaccountable institution is not really democratic. And unlike the supreme court, the Fed cannot claim a constitutional mandate. As a result, since the idea of central bank independence took off in the late 70s 4, the Fed has gone out of its way to show that it is being run by exceptionally responsible individuals.

Right now, they seem to think that the worst case scenario would be for them to cut rates and for inflation to then pop back up. While their fear is understandable, that is not actually the worst case scenario. Even excluding the dire political consequences of a recession, the human costs of an economic downturn would be worse than a dent to the Fed's credibility. Especially because the Fed can easily reverse course if they need to. The data suggest that the current inflationary episode is over. Even if the Fed thinks the economy is hot enough to sustain unusually restrictive financial conditions, it needs to start cutting if it wants to keep those conditions constant.

Footnotes

With all the caveats about the estimation method mentioned in the last post.

Technically it has a three-part mandate, but it has always ignored its statutory responsibility for low long-term interest rates.

see Blinder, Alan S. A monetary and fiscal history of the United States, 1961–2021. Princeton University Press, 2022.

ibid.