No, Trump's Tax Cuts Wouldn't add to American Growth

I will admit that I am a fan of the Economist. In my book, there are few better ways to spend a medium-length flight than reading an issue through cover to cover. Despite (or perhaps because) the fact that the articles often come from a slightly different political or economic philosophy to the ones I subscribe to, I rarely finish an article without learning something new, or at least having to reexamine an assumption that I hold dear.

With that in mind, when I got an alert two days ago for an article titled, Donald Trump's' tax cuts would add to American growth--and debt, I braced myself for something of a roller coaster. Had some respected economic thinkers analyzed the tax policies proposed by former President Trump in his current campaign and determined that they would lead to a structural increase in American debt, or, would the magazine come out with a scathing indictment of the deficit-busting policies that he prefers?

As it turns out, the answer was neither. Instead, the magazine dismissed the facts of Trump's deficit record, before citing two Trump-aligned economists (at least one of whom is famous as a hack) and a think-tank famous for making the types of errors Charles Schultze warned about when he said that "there is nothing wrong with the supply side that couldn't be solved by diving its claims by 10."

Therefore, I will try to offer an empirically grounded refutation of the claims and sources I found objectionable. While my hope that post will make its way back to the editors of the magazine would place too much stress on the word "unlikely," I do hope that whoever reads this article treats any claims about the beneficial effects of the poorly named Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) with the skepticism they deserve.

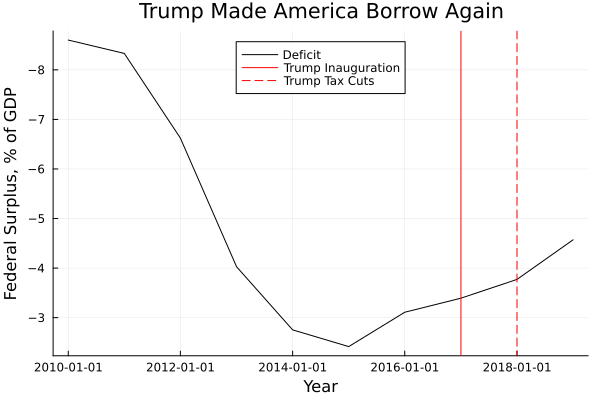

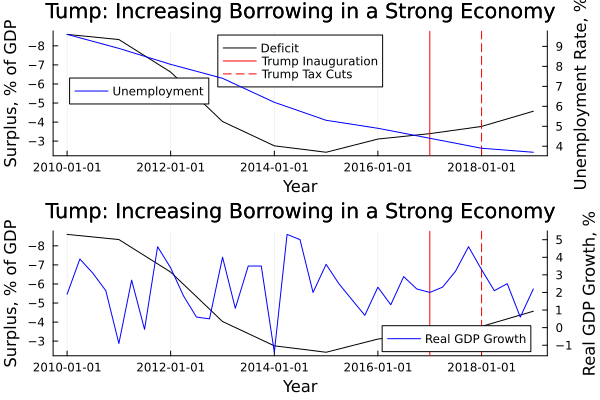

The Accumulation of Debt by the Trump administration was not just COVID

While the COVID stimulus undoubtedly skewed any metrics of fiscal balance during the Trump administration, by 2019 the country was already on the path to persistent trillion dollar deficits. This presented a major reversal from the slow, steady fiscal tightening that characterized the end of the Obama administration, which presided over a shrinking deficit as a percentage as GDP for seven of its eight years. In fact, by fiscal year 2019 the deficit had more than doubled since 2015.

That assertion is not, however, totally fair to the former President. After all, by 2019 the economy was much larger than in 2015. By that measure, the deficit had only expanded by 91 percent, from 2.4 percent of GDP to 4.6 percent. This deficit growth is, however, troubling, given the promises of the claims made by the acolytes of the TCJA about the growth it would bring.

No, The TCJA did not grow revenue through growth

In the article that caused this post, the Economist, in its most critical assessment of the law writes:

Mr Trump vowed that deregulation and tax cuts would unleash a torrent of economic growth; in reality America’s growth rate ticked up just slightly in the two years after his tax law went into effect, before covid erupted. But this extra activity did help to boost America’s fiscal revenues, offsetting some of the cost of the tax cuts.

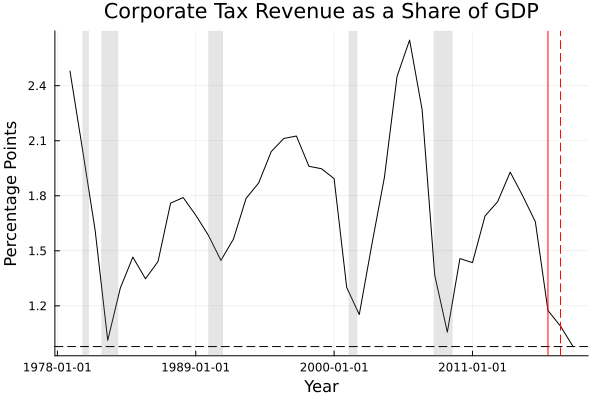

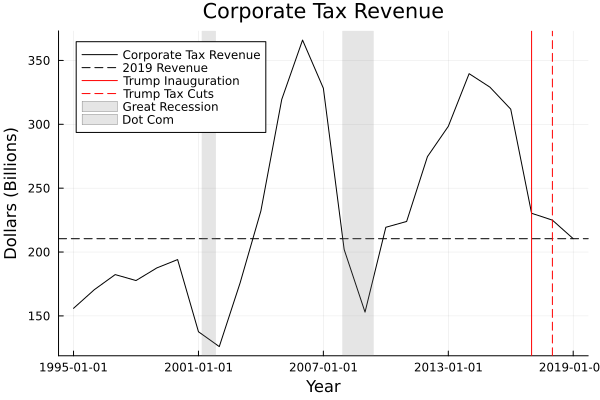

Unfortunately (for the country), the data shows that this couldn't be further from the truth. In April 2018, the CBO, then controlled by the Republicans who had written the legislation projected an 18 percent decline in corporate revenue. Instead, corporate tax revenue declined 31 percent. Not to worry, those same economists projected a 20 percent bounce back in 2019. Instead, corporate tax revenue declined 6.5 percent the next year. In fact, by 2019, corporate tax revenue had declined to less than 1 percent of GDP, the lowest level on record. Lower than during the Great Recession, or even the 1982 recession, which came shortly after Reagan passed what, contrary to Trump's oft-repeated claims, was the largest tax cut in American history.

In fact, the cut to corporate tax revenue was so drastic the IRS was collecting a similar number of dollars from corporations as it was during the Late Clinton administration, around two decades earlier.

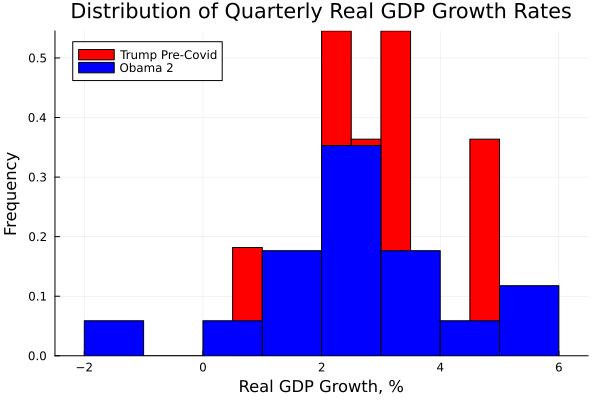

As can be seen in the two charts above, corporate tax revenue structurally fall during economic downturns. The Trump administration, before the pandemic, did not feature any. While it reached nowhere near the heights claimed by Trump and his acolytes, output grew and unemployment fell. In the years Trump was president before the pandemic, economic growth was roughly in line with President Obama's second term. An economy that Trump railed against as frequently as mentioned any policy issue during his 2016 run.

Going into more detail on his record of output growth and job creation, it become even more clear that, while he broke from President Obama's trend in borrowing, he was not able to affect any meaningful change in employment or output growth.

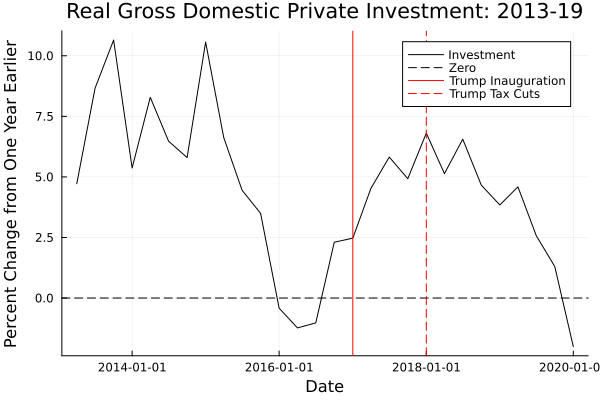

There is good reason for this lackluster growth. Proponents of the TCJA claimed that by cutting corporate tax rates, corporations would unleash a torrent of investment. That very much did not happen. Looking at the trend in real gross private investment, corporations did not plow their newly juiced after-tax profits back into the real economy. After the passage of the TCJA, the real growth of private investment slowed dramatically.

In fact, by the end of January 2020, Bloomberg was put out an article with this lead:

The longest pullback in U.S. business investment since 2009 shows little sign of ending, which could weigh further on the economy this year just as the once-gangbusters household spending that had been picking up the slack also slows down.

The headline in that Bloomberg article, Slump in Business Investment Gives Pause on U.S. Growth Outlook followed other detailed analysis of the behavior of corporations in the aftermath of the TCJA. Two months earlier, the New York Times, looking at Capital IQ data found no correlation between the tax cut a company received and investment behavior. In fact, the famously conservative (in making claims) paper of record felt comfortable including the sentence:

If anything, the companies that received the biggest tax cuts increased their capital investment by less, on average, than companies that got smaller cuts.

As companies showed no interest in investing their additional profits, it should be explained what they did. As can be seen in some of the longer term charts above, the Great Recession was extremely damaging, and the recovery started very slow. If companies had to load up on debt, they could have used their untaxed profits to retire debt and strengthen their balance sheets. The data, however, do not bear that out. From the first quarter of 2018 to the fourth quarter of 2019, non-financial corporations issued almost $400 billion more in debt securities than they retired or paid off. Again, that same New York Times article has the answer

From the first quarter of 2018, when the law fully took effect, companies have spent nearly three times as much on additional dividends and stock buybacks, which boost a company’s stock price and market value, than on increased investment.

Given the expanded borrowing, and weak investment, is it any wonder Trump would unleash some of his most potent tweetstorms against the Fed. The base of the economy his administration tried to build was a constant inflow into financial assets, so the modest increase in short term rates from 0.5 to 2.25 percent was a major threat.

All of this information was readily available to whoever wrote and edited the Economist article. Most of it was collected on American Bridge's public repository of Trump administration research reports. That the magazine did not cite any of it is made worse by the sources they did cite.

Weak Ethos

In making its argument, the Economist cites three people: Stephen Moore, a former Trump adviser currently a Fellow with the ultra-conservative Heritage Foundation; Thomas Philipson, the former acting chair of the Trump administration's CEA; and Erica York, the research director for the conservative Tax Foundation. While it should be completely unacceptable to cite Moore given his record as a dyed in the wool conservative with opinions so strong, facts cannot stop them, the other two sources are fitted to such an article. The problem is that neither should be relied upon as a main source, and both have significant, documented biases in the same direction. This error is compounded by the fact that, without a source of great renown to base an analysis on, the Economist should have at least solicited the views of someone not clearly identifiable as a conservative.

Stephen Moore Should Never Be Trusted

While a full documenting of Moore's lunacy is worth its own post, I still feel it is necessary to run through some of his highlights. As a full throated defender of Sam Brownback's disastrous tax policy, he got in trouble in 2014, when, feuding with Paul Krugman he made up figures relating job growth and state tax policy. Along with Arthur Laffer, he co-wrote a book called Trumponomics that promoted N. Gregory Manikaw--hardly a fan of liberal arguments about tax policy--to brand both of them "Snake-Oil Economists." On the subject of the TCJA, he felt comfortable enough to claim that it was paying for itself as early as September 2018.

Aside from his dogmatic approach to tax policy, his rank partisanship and cranky positions on other issues should be enough to banish him from the ranks of reliable sources on the impact of economic policy. After he and (a man whose famous 9-9-9 tax policy he helped design) Herman Cain were nominated by Trump to the Federal Reserve Board, the New York Times notes

Critics previously questioned Mr. Cain’s and Mr. Moore’s shifting views on interest rates, which both men said should be higher under President Barack Obama, when the nation was struggling to recover from the 2008 financial crisis, but now say should stay low under Mr. Trump, when the economy is growing. Both men have previously voiced support of a return to a gold standard, which the United States abandoned decades ago and few economists now support.

In additon to the Gold Standard, Moore has also expressed support for rolling back child labor laws, while being an active contributor to the radical Project 2025, a plan by Trump's most devoted followers to live out what Philip Wallach, an AEI senior fellow who it would be hard to characterize as anything other than a conservative, called "some kind of authoritarian fantasy."

Thomas Philipson is out of his depth

Philipson does not have Moore's record. Still, as as source on tax policy he is puzzling for two reasons: his expertise is not in tax policy, and his partisan devotion to the Trump administration's line during the pandemic caused him to willfully lie to the public. The first reason is simple. Looking at his CV, it is quite clear that Philipson is primary a health economist. While one does need (and indeed, in some cases, it could be detrimental to have one) a PhD in economics with a focus on taxation to offer insight into the subject, but as a primary source in an Economist article, I would expect something more.

Much more worrying is Professor Philipson's behavior during the pandemic. In 2019, while he was the acting as the CEA's chairman, it produced a report concluding that a flu-like pandemic could cause hundreds of thousands of deaths and trillions in economic damage. In the early days of the pandemic, still in his acting capacity as CEA chair, Philipson downplayed the economic and health risks Covid-19, projecting near-zero costs.

This behavior casts doubt on his trustworthiness, and in combination with the Economists' reliance on Moore, severely weakens the article. Still, they are not the only authorities cited, so it is now time to turn to Erica York and the Tax Foundation.

The Tax Foundation's backward outlook

Unlike Moore and Philipson, York prefaced her comments with hedges and offered offsetting information readily

Mr Biden’s approach offers a counterpoint. He has called for a range of tax increases, including raising the corporate rate from 21% to 28%. “That may be counterproductive,” says Erica York of the Tax Foundation, a think-tank. Ms York and her colleagues estimate that Mr Biden’s tax proposals would lower America’s debt-to-GDP ratio but also shrink the economy by 1.3%, whereas Mr Trump’s tax cuts would, if permanent, push up debts but expand long-run GDP by 1.2%. It is not a simple trade-off either way.

The fact that York donated $5 to Biden's 2020 campaign also speaks to her position as a counter to--and validator of--the opinions offered by Moore and Philipson. And while York's analysis is likely internally coherent, and the Tax Foundation is sufficiently well respected to come with an assumption of good faith, their long-documented conservative and anti-tax biases make the combination of sources chosen by the Economist so pernicious.

In publicans like the Washington Post, New York Times, and Politico, publications with a strong reputation for being very careful in publicly identifying political actors with a conservatism, the Tax Foundation is routinely identified as "conservative" or "business friendly."

Evidence for this bias in their model can be seen in the organization's bias towards lower corporate tax rates. For example, in 2008, they launched a campaign called "Compete USA," which argued that the United States had to cut statutory corporate tax rates due to lower rates in other OECD countries. It conveniently ignored the fact that the nature of our tax code allowed for almost all multinational companies to easily shift profits and take deductions to an extent that our statutory rate had little meaning.

While this campaign was launched well before York started at the Tax Foundation, I can speculate with some authority that the model they cite is structurally similar to the one they were using when they launched that campaign, or when they offered praise to Paul Ryan's draconian budget plans, or when they offered specific praise of the TCJA.

To start with, the economic models that map onto real world data with sufficient complexity to specific numbers as policy outcomes are massively complex, and therefore a pain to rewrite from the ground up. In September 2018, the same month Moore claimed the TCJA was paying for itself, then-President of the Tax Foundation, Scott Hodge offered testimony to the Joint Economic Committe, emphasizing how the cuts to the statutory corporate tax rate would spur increased corporate investment and growth. Since then Hdoge ceded the Presidency to Daniel Bunn, a former staffer to conservative stalwarts Mike Lee and Tim Scott. Therefore, I highly doubt that they have fundamentally rewritten their model to take into account the structural implications of the investment response to the TCJA. Instead, they have probably just reestimated some parameters, which may reduce the size of their errors, but will not reduce their direction.

That is not to say the Tax Foundation should never be listened to. They employ an enormous number of hardworking and qualified experts to come to well reasoned positions on tax policy. They should just not be listened to in isolation, and they certainly should not be listened to in combination with a Trumpist true believer and an extremely conservative alumnus of the Trump administration.

By structuring the authoritative sources for their article this way, the Economist pushed an agenda out of step with the empirical evidence. I hope that they do better in the future, and I hope that whoever reads this is more skeptical of claims about the benefits of the TCJA, or originating from Moore, Philipson, or the Tax Foundation.