How I would structure Defence Contracts

Day 12, and the impulse to doomscroll has only gotten stronger. While government services are being dismantled with what seems like malicious glee, writing about defense contract reform feels a bit like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. But imagining a better world is always worthwhile, especially in small ways. Because small things are doable, and as Gandalf so wisely said,

I have found that it is the small everyday deed of ordinary folks that keep the darkness at bay.

The idea for this post came to me earlier today when I was digging through the show notes for the Acquired Lockheed Martin episode. Towards the end, Ben and David highlighted a persistent problem in defense contracting: contractors are actively disincentivized from delivering projects on time and within budget. The culprit? The cost-plus mechanism that dominates defense contracts.

Here's the basic math (which is, sadly, not as oversimplified as you might hope). The price ($P$) we pay for defense goods and services is calculated as a fixed markup ($\tau$) on the development and production cost ($C$): $$ P = (1+\tau)C $$ A contractor's profit ($\Pi$) is simply $\tau C$ – a constant fraction of the cost. While the profit margin is fixed, the total profit is theoretically unlimited. Basic economics would suggest this incentivizes companies to maximize costs. Or they would be, except for the fact that they are playing a repeated game, and need to keep their eligibility1. But with only five prime defense contractors, that is a pretty low bar to clear.

One commonly suggested solution is a fixed cost contract. These contracts are simple, the government agrees to pay a fixed amount. If the contractor can deliver for less, they can keep the difference. If they cannot, they have to eat the loss.

This is intuitively attractive, and, especially for commodity products, it should be the approach adapted. But where innovation is concerned, there should be some leeway for at least two reasons. First, genuine innovation involves fundamental uncertainty – costs can exceed projections for legitimate reasons. While private firms can and should bear this risk, they have much more flexibility in how to market their innovations While government's monopsony power in defense procurement exists for a good reason--you don't exactly want Lockheed auctioning off advanced stealth technology--there's strategic value in maintaining a profitable defense industrial base. We don't want individual contracts to risk bankrupting otherwise capable contractors.

That is where this idea comes in. What I'm calling split-risk contracts2. These could be structured in such a way as to guarantee a company positive profits, but have the marginal rate of profit depend on the production cost relative to the target production cost, $C^*$. For example:

$$ P = (1 + \tau \cdot \frac{C^*}{C}) C $$

This method essentially has a fixed dollar profit amount of $\tau C^*$, eliminating the incentive to increase costs, while using financial markets' preference for higher-profit margins to incentivize the prime contractors to come in under budget, without forcing them to take the risks of catastrophic failure a fixed-price contract would.

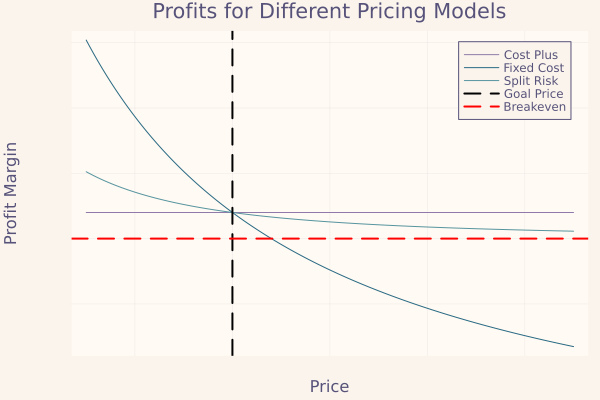

And because no blog post of mine would be complete without a nice plot, this is what the profit margins would look like under all three contract pricing mechanisms that are structured to meet the cost plus profit margin at the same production cost. It should be noted that under this structure, the fixed price contract had to have a higher target price.

Our democracy is under attack, our government is being looted, and the people least able to protect themselves are the targets of state-sponsored violence. Incremental reform will not change that. But the only way to make sure that the American people never again turn to fascism is to make sure that democracy delivers them optimism about the future. And a big part of optimism about the future is the ability to achieve big things. But we cannot achieve big things if we are constantly wasting time, money, and focus on small inefficiencies. So the incremental work to reduce those inefficiencies is vital.

And at worst, the deck chairs being arranged properly could reduce the risk of someone tripping on one as they run to a life boat.

Footnotes

For a given public defense contractor, what they are actually maximizing is the present discounted value of all of their future profits. Those profits consist of two things: their profits in a given time, and their eligibility to continue playing. If $C_t^* $ is the amount the contract was supposed to cost, then the contractor's eligibility to compete for another one, $\mathcal{P}[C_{t+1} \neq 0] = f(\frac{C_t}{C_t^*})$ where $f' < 0$. 2: To be clear, I am not claiming I invented these. The only research I did before writing this post was making sure that I was not suggesting the way defense contracts are currently created.